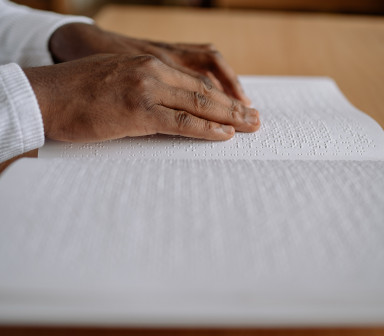

Braille is a tactile reading and writing system. It opens up the written word to blind and visually impaired people.

Here are ten facts about braille to help you learn more about this 200-year-old code which is still a key to literacy and independence for thousands of blind and visually impaired people around the world today.

1. Braille was developed by Louis Braille in the 1820s when he was a pupil at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris.

Before he developed his revolutionary code, various systems mostly using raised print letters were used to help blind people read. For example, Valentin Haüy’s tactile books featured embossed versions of the Roman alphabet. Louis Braille’s code was designed for tactile recognition – not visual recognition – and finally enabled blind and visually impaired people to also write independently.

2. Braille is not a language.

It is a tactile code enabling blind and visually impaired people to read and write by touch, with various combinations of raised dots representing the alphabet, words, punctuation and numbers. There are braille codes for the vast majority of languages – some symbols have different meanings for aspects such as accented letters, depending on the language. In its simplest form one letter is represented by one symbol, however contracted braille provides some shortening.

3. It’s recommended to learn braille by touch if you’re losing your vision but still have some sight remaining when you start.

As a tactile code, it will only be of use if you can read and write it via touch if sight is lost completely or reading large print is no longer possible.

4. Braille uses much more space on a page than a sighted writing system.

Contracted braille, where a braille cell may represent a whole word or part of a word, is the usual system that helps to save space and also allows for quicker reading and writing. Find out more about contracted braille.

5. Braille isn’t used to transcribe and write books and publications alone.

It is also used on signage in public spaces, such as lift key pads, door signs and on restaurant menus, and for labelling everyday items like medications. It is also used as an accessible format for various documents, such as bank statements. This helps blind and visually impaired people to identify objects quickly, work out where something is when out and about, keep safe and maintain their independence.

6. Today, electronic braille notetakers and refreshable braille displays enable blind and visually impaired people who know braille to browse the internet and read webpages and email, and save and edit their own written work.

7. A number of hugely popular classic games have adapted braille versions.

These include Monopoly, Scrabble and Uno. Braille playing cards are also available, enabling blind and partially sighted people to enjoy these games too and also play along with sighted friends and family. LEGO have created LEGO Braille Bricks as a playful way to teach braille.

8. Practising reading and writing braille regularly can help to improve reading speed.

Just like mastering print reading and writing, sequential learning and practice is required for braille learning.

9. There is no average timescale to learning.

It varies from person to person. Braille takes time to learn due to the various dot combinations and the need for a person’s fingers to get used to identifying the dots by touch.

10. Not all blind and visually impaired people use braille.

It can take a while to develop the touch sensitivity you need for braille. This may make learning braille at an older age or with other health conditions affecting sensitivity in fingers more difficult.

As an adult, choosing to learn and use braille is very much down to individual preference. For example, someone who loses their sight as an adult may prefer to stick to digital assistive technologies using specialist software such as screenreaders, video magnifiers or recorders.

However, there are important and significant literacy benefits to learning braille which can allow for greater freedom and independence. Many blind and visually impaired people find it very useful in the workplace. People who are deafblind also cannot use audio formats making braille all the more important as a means for literacy and communication.

Learn more about accessible formats produced by the Scottish Braille Press.