An Army veteran who was involved in the Western Desert Campaign in Africa and the Normandy Landings recalls his experience of serving in harsh and unforgiving terrain throughout the Second World War.

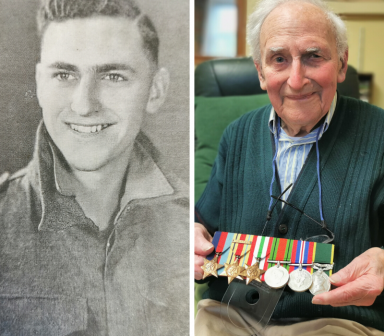

John McOwan, of Peebles, was an instrument mechanic in the 7th Armoured Division, famously known as the Desert Rats, from 1939 to 1946.

John, now aged 99, joined the Territorial Army in January 1939 aged 17. When the war broke out that September, John was one of the first to be called up. After spending several months outside Edinburgh on coastal defence, John was transferred to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) as an instrument mechanic, which eventually became the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) in 1942.

“Before the war, I worked in my father’s jewellers and clock making shop. Because of my experience repairing clocks, they decided to put a round peg in a round hole,” said the father-of-one.

'The sand would sting our skin like sandpaper'

John embarked on a long journey which would see him spend several years in an environment far from home. He said: “We arrived in Mersa Matruh in Egypt after travelling by boat and train and then travelled to Abassia Barracks in Cairo where we were stationed in a base workshop for one month of training.” In April 1940, the 7th Armoured Division started their journey through the desert.

He said: “We were a mobile workshop, so as the armed division moved up and down the desert, we followed close behind to maintain all of their vehicles and equipment.

“They say the Sahara desert is one of the most inhospitable terrains to ever have to exist in. During the day it was searing hot and by night it was freezing cold. If we were caught outside during a sandstorm, the sand would sting our skin like sandpaper.”

The Desert Rats spent years in the desert defending Egypt from the Germans and Italians, who together were known as the Axis forces, during which they faced many battles. “We travelled all the way from Cairo to Benghazi which would have been around 1000 miles,” said John. “It was a long way to go on sand.”

“We would advance and the Germans would push us back, then we would advance again and get pushed back.”

Then, in May 1942, the 7th Armoured Division encountered an attack in Gazala, North Africa, which saw the British, South Africans, Indians and French battle German and Italian forces.

“The Germans and Italians had outdone us and we had to retreat. Whenever we lost a battle they would say there’s a ‘flap on’ which meant we had to retreat quickly. We piled all our stuff in the vehicles and got out as quickly as we could,” said the grand-father-of-three and great-grandfather-of-three.

“One particular time, there was a flap on and we were told ‘right get out, we’re retreating.’ So we set off in a convoy unit which comprised of two great big six-tonne machinery tanks, one of them was from the First World War. It was always breaking down so we had to tow it which wasn’t an easy job in the desert.

“The tank broke down and we all had to come to a halt. All the troops past us and we were left in the desert. We thought ‘right we need to get this repaired and get out of here before the Gerry (Germans) arrive’.

“We started working on the tank but we couldn’t get it fixed, then we started to see dust clouds form from vehicles approaching us in the distance. We thought it was the Germans but luckily it was one of ours. He stopped to tell us that Germans were just over the ridge and we better get out of there.

“He cleared off and we thought about abandoning the vehicle, but we received orders to put it on tow. We managed to get away but we were very lucky we didn’t end up in the bag – which we used to say when someone was taken prisoner.”

'Stop retreating and fight to the death'

For several months, the division retreated further through the desert, eventually coming to a halt in El Alamein.

“Churchill sent a message to stop retreating and fight to the death. Churchill appointed General Montgomery to take over the Eighth Army, which our division was a part of. He was very popular with the troops.

“Montgomery decided that he would put the wind up the Germans and Italians by creating a feint. He gave the impression that we would advance from the south and set up dummy tanks to trick the Germans and Italians. Then the main attack was from the north.

“They surrendered in their tens of thousands. It was miraculous.

“At the beginning of the war, we suffered all sorts of defeats. Germans advanced from lots of different countries and battleships were sunk, so we were hungry for a victory somewhere.

“Eventually, when Alamein came and the desert rats chased the German Africa Corps out of North Africa we were hailed as great victors. It was the first victory we had.”

The division travelled from Tripoli to Salerno in Italy in September 1943 and were part of operation Avalanche, a landing during the early stages of the Italian campaign. After a few months, John and the rest of the division were sent back to the UK for refitting.

The Normandy landings

Before long, John went on to face the Normandy landings.

“Before the Normandy invasion, all of the troops were put into sealed camps so that no information would leak about when and where the invasion would be.

“The Germans thought we were going to invade at the short crossing at Cali. We only discovered we were heading for Normandy once we were nearly there, up until then we didn’t know where we were going.

“They kept it very secret to trick the Germans. In fact, they believed it so much that Hitler refused to accept that the landing was in Normandy, he thought it was a ploy.

“This helped us a great deal of course because, by the time the reinforcements arrived, we had established a beach head in Normandy.

“When we sailed across the channel, it was an awe-inspiring sight because there was thousands of ships in the English Channel, we could almost have walked across them all. I thought to myself, if the Germans came over now we’re all sitting ducks.

“All I could think was the sooner we land the better. We had become too much of a target.”

John landed on Sword Beach in Normandy on D-Day +4. “We were on a landing craft ship. Once we landed, a ramp went down and we drove onto the beach. I actually got ashore without wetting my feet so I was lucky.

“Our job was to follow the division and look after their equipment, so once we were ashore, we had to get off the beach as quickly as possible and set up a workshop.”

After several weeks of being stationed just off Sword beach, allied forces pushed the Germans out of France, through Belgium and into Holland. As the troops advanced, John and the rest of the unit were never far behind.

John's return home

As the war drew to an end, John was sent to Hamburg, Germany. “We knew the Germans were on their last legs for a while but they kept fighting until the bitter end,” he explained.

“The end of the war was a bit of an anti-climax. We had to wait to be demobbed, it took quite a few months before all of the troops were returned to the UK.”

The Desert Rats famously led The British Victory Parade in Berlin in July 1945 and their achievements were recognised by Winston Churchill who said in his speech: “Dear Desert Rats! May your glory ever shine! May your laurels never fade! May the memory of this glorious pilgrimage of war which you have made from Alamein, via the Baltic to Berlin never die!”

John returned to his hometown of Peebles in June 1946 where he took over his dad’s jewelers and clock making shop until he retired in 1990.

John, who now lives alone, was diagnosed with macular degeneration in 2005 and has been supported by Scottish War Blinded since 2016.

“Scottish War Blinded has transformed my life. Being able to meet fellow veterans and share common interests has given me confidence and more enjoyment to life,” John said.

John is eager to hear from fellow Desert Rat veterans and would love to reminisce about time spent in the Desert. If you were a Desert Rat or served in Africa, please contact Eilidh McCartney on 0131 229 1456.