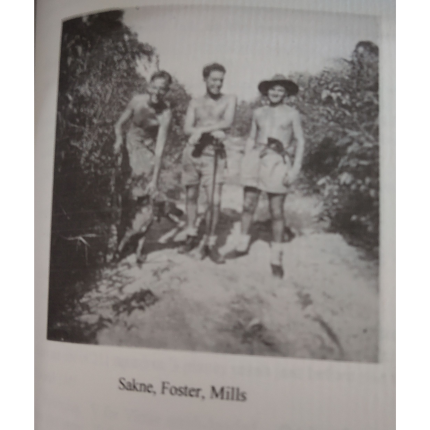

As we commemorate VJ Day in 2025 and the end of the Second World War, we are honoured to share here the second of the late Gordon Mills stories, titled 'Going Home'.

Gordon, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 99, was a proud veteran who served in Burma during the war. In later life, he became a regular at Sight Scotland Veterans’ Linburn Centre, which he loved! From gliding and skiing to archery and 4x4 driving, Gordon threw himself into every activity often with his wife by his side, camera in hand.

Recently, Gordon’s wife, Yvonne, found stories Gordon wrote recalling his time in Burma and his travels home after VJ Day.

We are honoured to share Gordon’s recollections, 'Going Home', below, in both written and accessible spoken audio formats, as both a tribute to his service and a celebration of his life.

Going home

My diary for a long forgotten reason ends in September 1945 and now I have to rely on ancient memories. I do remember that we were supposed to be on our way home from Burma and we knew, with insufficient ships for that purpose, the journey could be long and very slow. We travelled in open trucks south and ended that long first day in Trichinopoly.

A few days later we were back on the open trucks heading for Visagapatam. On opening our - never to be forgotten - American K rations, I will never know if it was the sight or the smell of the Transatlantic food that brought hordes of monkeys out of the edge of the forest and on to our speeding vehicles, snatching what they could as the trucks hurtled on. They snapped and snarled, flung their arms about and showed their teeth. It had been – I think - a spontaneous raid and the monkeys won. Or did they really? I cannot imagine what they thought and what they did when they opened the little boxes with the meat inside cans, and I still wonder about the dozen sheets of toilet paper and the small packet of four cigarettes found in every box. After the skirmish, Peter Beecroft wondered how the animals would light their fags without matches. “Perhaps they had lighters,” he said.

Eventually we arrived at Visagapatam none the worse for wear except for a few scratches, now covered with iodine. About a week was spent in Visagapatam wandering, looking at temples, in particular one with a huge carved bull which apparently bleeds from the same spot every year, Now isn’t religion wonderful? Our last journey by road was to Tanjore, a bit further south but no nearer home.

That was the road journey over as the next part was to be travelled by rail to Bombay. That part of the journey home took three days of viewing the countryside, sleeping, and gambling. At various stations we were entertained by fakirs twisting their malnourished bodies into impossible positions then sticking skewers into those already broken. As an encore they twirled very quickly before coming to rest before a small audience, taking the skewers out and showing the inquisitive that they had not lost a drop of blood. A small bowl was then passed round into which the bemused spectators sometimes dropped an anna or two.

Unlike the New Zealand meat ship, the Steamship Tamaroa with its stinking atmosphere, which I had travelled on in July 1942, we boarded the Georgic, a modern luxury liner converted to a troopship. We actually got cabins. We were passengers, not crew, not ships gunners, no dog or any other watch - the war was over. No need for blackout on this ship, no duties, no sweat box because of sealed portholes.

So we crossed the Indian ocean into the Red Sea and onto Port Tewfic and on to Suez where we had once been stoned. Then the 100 miles of the Suez Canal passing the spot on the Great Bitter Lake where Arthur Danks and I had been shot at less than two years before. We sailed very slowly through the small Bitter Lake and into Lake Timsah where the playboy King Farouk moored his private yacht. Onwards past Ishmalia, passing El Ferdan, past the railway bridge that took me to Palestine only 18 months ago (it seemed like years) and where we had been inoculated with anti-Bubonic serum nearly two years before, then slowly and carefully north to Port Said and into the wide Mediterranean Sea. Sailing through the Mediterranean in December was pleasant, and made me think about the people who could afford luxury cruises – they would soon be booking, now that the war was over.

On past Gibraltar (Gebel Tarik) and out into the Atlantic and the Bay of Biscay where all hell broke loose. I had never dreamt a December storm in the Bay of Biscay could be quite so violent. We, the military passengers, including the man who had been in charge of the Burma campaign, General Sir William Slim were in danger. The man who led the Forgotten Army, and forgotten we were as most of the armaments and other supplies went to support the war in Europe with the dregs eventually reaching Bill Slim’s forgotten army in Burma.

(After that little diversion back to Burma, we now return to the good ship Georgic.)

I cannot remember how long we were battered by that December storm when we could do nothing to stop lifeboats and life rafts from destruction. We the passengers and, I must believe, the crew, would also be washed overboard. Huge waves towering above the giant liner Georgic, black waves with white tops smashing down on the ship: breaking lifeboats and life-rafts from their moorings and smashing them to pieces before giving them to the ocean.

I was seasick and could not eat for about 24 hours – I lay on my bunk for most of that time feeling sorry for myself. When I could move about the ship and looked out from a heaving deck it seemed the end of the world was near as waves as high as five storey tenement buildings appeared about to crash on top of us, but somehow the ship, tottering and heaving, seemed to slide up the side of the wave, and as we thought how marvellous it all was, another giant wave would take us by surprise and crash down on the deck which was itself like a raging river of boiling water when the ship was on a level keel for a few seconds. Then, as the ship tilted, a cataract flooded down the side.

Most people aboard were seasick including hardened members of the crew. A man in my cabin could not get out of his bunk for four days until we docked. He looked, and no doubt was, seriously ill – there was no use trying to contact the ship’s doctor as he was probably sea-sick too – and, in any case rankers did not have the doctor coming to them. They were expected, no matter how ill, to attend sick parade (what nonsense – imagine having to parade if you were ill). Strange are the ways of the armed services!

That storm for many of us must have been one of the worst parts of our lives, and I do not exclude the war from that hypothesis.

Arriving at Liverpool early on Christmas day 1945 did not worry the Scots among us as it still was not a holiday in Scotland. However, to be home on leave for Hogmanay was something to look forward to – something very special.

Written by Gordon Mills, 18 March 2015